Stakeholder Capitalism or Economic Totalitarianism?

The economy has been dominated by global institutions over the last few decades. But now things are changing. Here's what's at stake.

Yesterday was a big day in the global economy. But not for the reasons you’re probably thinking.

The Trump Administration’s long-awaited tariffs officially went into effect. But while most people are focused on the costs associated with those tariffs, that’s not the full story. By implementing tariffs, the United States has signaled that business as usual is over for the global economy.

A new economic world order is in the process of taking shape.

Prior to World War II, the world was governed by bilateral trade agreements much like we’re starting to see re-emerge today. Countries acted in their own self-interests, issuing tariffs or engaging in trade only when it was advantageous for them to do so.

All of that changed after the war. With the emergence of international organizations like the United Nations and the Bretton Woods financial system, countries became increasingly integrated with one another. They started to focus on the collective good rather than the well-being of the individuals they governed.

This culminated with globalized free trade at the end of the 20th century. The World Trade Organization gave any country access to favorable trade terms in the global market – including China – while agreements like NAFTA led to acute job losses in the United States.

While there are certainly benefits to free trade, it’s not all rainbows and butterflies. As the United States began to implement policy positions of these international organizations, the well-being of individual Americans declined. Jobs were shipped overseas while businesses began offshoring their profits. In an effort to promote the good of society the individual had to take a hit.

Now it appears that the era of free trade is coming to an end. Trump’s tariffs signal America is open for business, but it isn’t going to tolerate dictats from above. As a result, a new economic order is poised to fill the void that America’s leadership within these organizations is now creating.

A competition is already in the works to figure out what comes next. It’s likely you’re already aware of competition between the United States – a capitalist country that promotes free enterprise – and China – a communist country that promotes state-sponsored enterprises. What you might not be aware of is that there is also a competition within the future of capitalism itself and this is taking shape.

The American system of shareholder capitalism was the winner after the second world war but as free trade and globalization took shape a new economic system began to emerge in Europe – stakeholder capitalism. While this economic system fancies itself as a more compassionate and socially just form of capitalism, the absence of individual freedom to make independent economic decisions – an essential element of capitalism – suggests this is an entirely different economic system.

This new system carries many of the hallmarks of communism but is supranational in nature. Groups of technocrats at non-governmental organizations – rather than government bureaucrats – are deciding what’s good for individuals and how they should participate in the economy.

While this type of system isn’t centrally planned like the communist governments of the Soviet Union or China, it is centrally managed. Policies are promoted to shape specific outcomes and those outcomes are for the good of the collective rather than the interest of the individual.

At the forefront of this competition for global economic power is the World Economic Forum. Up until a few years ago I, like most people, thought the whole globalist conspiracy coming out of Davos was just that – a conspiracy. But COVID awakened me from what I can only describe as a long, deep slumber.

Once I started investigating the philosophy underpinning the policies promoted by credentialed experts at the World Economic Forum, I started to see manifestations of the new system they’re trying to create. Maybe there was something to the conspiracy after all. There is an agenda to reshape the global economic order and that new order is not in the benefit of the United States – or any individual who loves to buy, sell, and trade whatever they please.

This essay will dive into a brief history of the World Economic Forum and its core economic beliefs. It will evaluate stakeholder capitalism and argue that while the ethos of respecting people and the planet is well-intended, the implementation of the policies to make that happen are inherently totalitarian in nature. What the conspiracy theorists had warned, and what we’re now starting to see emerge, is a global government where select stakeholders – rather than individuals – are the only ones who have a stake in the economy.

The information I share below might not be new to you but it is new to me. Even though I studied international relations in college and knew about the World Economic Forum, I never once evaluated the organization’s claims. But now that I am in a different headspace to evaluate these claims – and have lived experience to contextualize them rather than rely on college textbooks – I can critically think about what all of this means for the economy moving forward.

The goal isn’t to convince you that there is a global conspiracy afoot. The goal is to make you curious about what is happening in the world and ask questions about why it is happening. Why is becoming a “global citizen” more important than being an individual in the country you currently live in? Why have imagined “communities” become so heavily politicized? And why are we spending money on things that make us less of a stakeholder in the physical communities we actually live in?

I may not be able to provide the answers to these questions in this essay but by laying out the philosophy underpinning global organizations – specifically the World Economic Forum – I hope you can evaluate the information for yourself and come to your own conclusion.

Given what I’ve studied about capitalism on my own, I don’t see how it’s possible for individual freedom to coexist in a world where a collection of disparate stakeholder interests reign supreme. Will this new economic order supplant individual freedom in order to benefit the common good? And if it does, how will this system be any different than the totalitarian systems that emerged in the past?

This essay dives into:

⚡ Why the global economy is shifting away from free trade and toward a new, centralized system

⚡ How international organizations are reshaping capitalism — and what that means for your individuals

⚡ Why stakeholder capitalism is about managing and controlling an economy rather than making it more inclusive

⚡ How managed economies fared in the past and what that could signal for the future

☕ Support independent analysis like this to get a different perspective.

Your support makes it possible to ask thought-provoking questions. Become a subscriber to access new articles and contribute to the conversation.

Don’t just consume the news — help shape it.

The World Economic Forum was founded by Klaus Schwab in 1971. Based in Switzerland, the WEF is an international organization that brings governments, businesses, and civil society together to make the world a better place.

1971 is one of the most important years in modern economic history. In August of that year, President Nixon announced that U.S. dollars would no longer be converted into gold. That announcement formally ended the post-World War II Bretton Woods system and within a couple of decades, it ushered in a new economic order marked by free trade and globalism.

That same year, a German man published a book titled Modern Enterprise Management in Mechanical Engineering and opened the offices of what was known as the European Management Forum. That man was Klaus Schwab and his vision for what the new world order would look like became known as the World Economic Forum.

According their website, the World Economic Forum’s mission is to:

Bring together government, businesses and civil society to improve the state of the world

It does this through its famous Davos summit. Every year the who’s who in world affairs reports to the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos to discuss the state of the world. While Davos is marketed as a platform for collaboration between world leaders, business leaders, and academicians, in practice, it’s a venue for global governance. The policy initiatives that come up at Davos aren’t just discussed, they’re taken home and implemented.

Before we dive into the implications of this, it’s important to first talk about what the World Economic Forum’s vision is and how the organization wants to reshape the global economic order in its image.

In Schwab’s 1971 book Moderne Unternehmensführung im Maschinenbau or Modern Enterprise Management in Mechanical Engineering he argues for greater stakeholder representation in business. He suggests that stakeholders – rather than just shareholders – were key to long-term growth within companies.

This idea was a rebuttal to Milton Friedman’s theory of shareholder value that came out the year prior. In a 1970 essay published in The New York Times, Friedman made the argument that businesses had no responsibility to the public. Its sole raison d’etre was to generate profit for its shareholders.

Schwab suggested that a shareholder-centric business left out key stakeholders that were part of the value chain. This included employees, vendors, and the local community where a business operated. His theory on shareholder value offered a different approach to business. And in doing so, he made the case for an entirely new economic system.

According to the World Economic Forum, an economic system that is inclusive of all of the stakeholders that participate in it is called stakeholder capitalism. It defines the system as:

A form of capitalism in which companies do not only optimize short-term profits for shareholders, but seek long term value creation, by taking into account the needs of all their stakeholders, and society at large. (WEF)

For Schwab, stakeholder capitalism is a way of connecting businesses with their communities. This represented a new way of doing business in Europe as it emerged from the rubble of war:

This approach was common in the post-war decades in the West, when it became clear that one person or entity could only do well if the whole community and economy functioned…This fostered a strong sense that local companies were embedded in their surroundings, and from that grew a mutual respect between companies and local institutions such as government, schools, and health organizations. (WEF)

If Friedman is the American view of capitalism after Bretton Woods then Schwab represents the European perspective. His interpretation of capitalism is influenced by where he was raised – in Germany. The economic model that emerged in Germany following the war was highly collaborative. German workers had a say in how companies operated and in exchange, received social benefits like health care when companies did well.

This economic system is referred to as a social market economy or Rhine capitalism. This system is characterized by collaboration instead of cut-throat competition. While this isn’t the only economic system to emerge in Europe, it has become one of the more dominant ones. Within the span of a century, Germany has gone from total economic collapse and political disunification to being the powerhouse of Europe. Whatever the Germans did during the second half of the 20th century, it worked.

This ethos of collaboration and social responsibility encapsulates the idea of stakeholder capitalism promoted by the World Economic Forum. While many people would agree that incorporating the needs of stakeholders into business decisions is a good thing, the implementation of stakeholder capitalism in practice has been an entirely different story.

At its core, stakeholder capitalism is not capitalist in nature. Instead, it is a collective approach to economic management. Rather than being a form of communism governed within a state, stakeholder capitalism represents a form of supranational statism that governs from above. The interests of individual states and the citizens that reside within them become secondary to the interests of the global collective good.

Schwab’s vision didn’t stick initially. But after a rebrand, the World Economic Forum has found a way to integrate stakeholder capitalism into private businesses, changing the meaning of capitalism and transforming the global economy.

Klaus Schwab’s vision for the future was one of many visions that emerged during the 1970s but it didn’t stick. His original interpretation of stakeholder capitalism lost out due to globalization. As the economy globalized, communities lost ties with the businesses that operated in them. Without that connection, businesses didn’t have a responsibility to anyone but their shareholders.

After the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, things changed. Decades of globalization and deindustrialization finally caught up with the economy. This created a window of opportunity for Klaus Schwab to try again to make stakeholder capitalism the economic system of the future.

Instead of being a victim to globalization, the World Economic Forum has repositioned itself to be the solution to it. With myriad social, political, economic, and technological issues facing the world today, the World Economic Forum provides a platform for leaders to come together and collaborate on solutions.

In his 2021 book Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy that Works for Progress, People and Planet, Schwab offers a new, more practical framework for integrating stakeholder value into the economy.

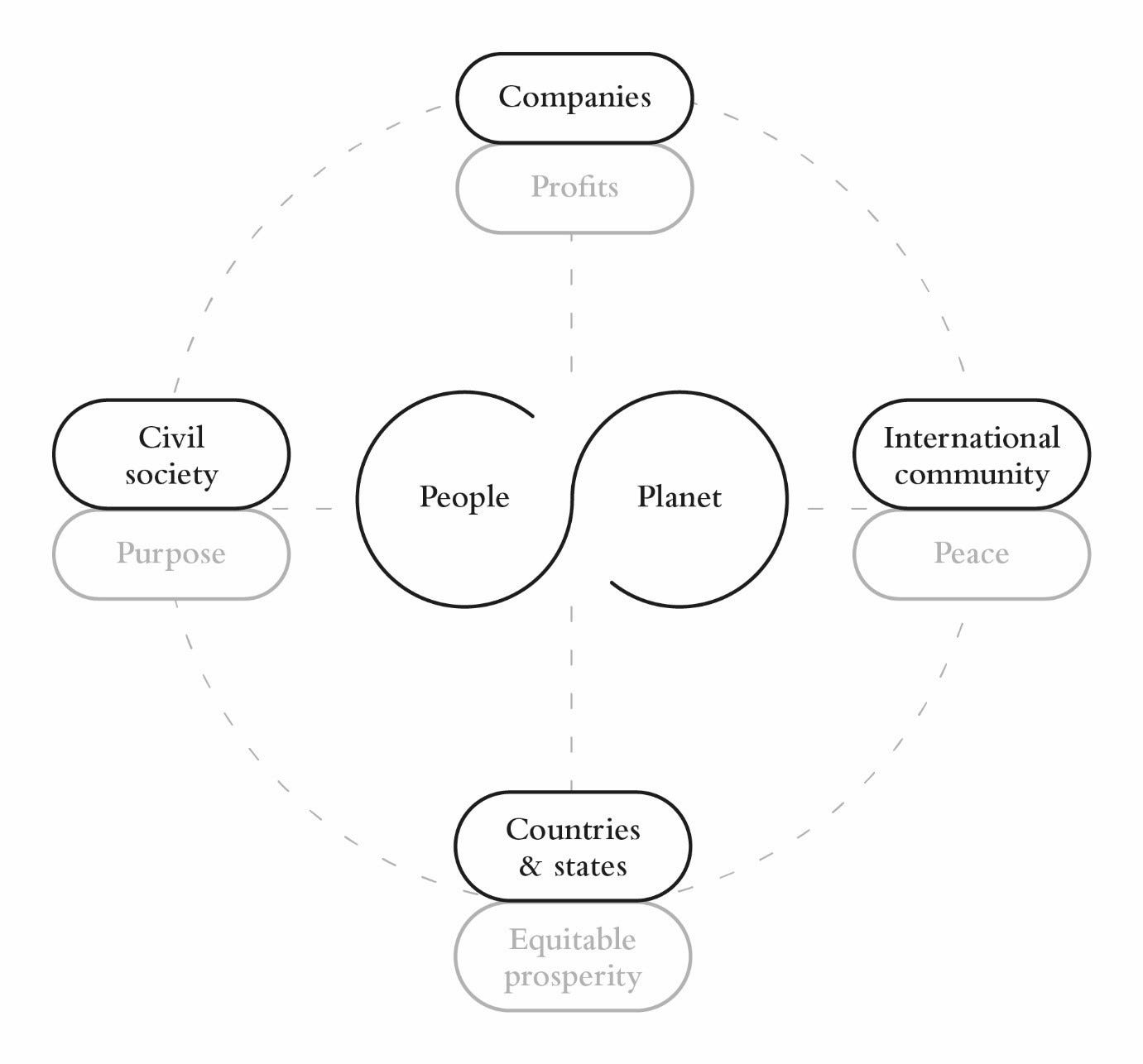

According to Schwab’s updated definition of stakeholder capitalism there are four primary stakeholders that should come together to solve two key problems: the health of the planet and the well-being of the people that occupy it. Those stakeholders include:

Governments

Civil society

Companies

International organizations

It’s worth noting that ‘individuals’ are not represented as stakeholders whose interests need to be accounted for. Rather, individuals are part of larger entities – companies, universities, or countries. Individual interests don’t exist, but rather the collective interests of different stakeholders do.

The idea of stakeholder capitalism has proliferated, but it has not been fully embraced. It underwent yet another rebrand just a few years ago. And this rebrand is why the World Economic Forum has come under fire from conspiracy theorists. Just as the global economy was locking down, the World Economic Forum was making the case for resetting it.

The timing may have been coincidental but it couldn’t have been any better.

In its 2019 Davos Manifesto, the World Economic Forum didn’t just promote stakeholder capitalism, it redefined the role of business within an economy. Instead of being an engine of profit generation for the greater good, businesses are now supposed to be vehicles to coordinate stakeholder interest:

The purpose of a company is to engage all its stakeholders in shared and sustained value creation. In creating such value, a company serves not only its shareholders, but all its stakeholders – employees, customers, suppliers, local communities and society at large. (WEF)

To make this happen, the World Economic Forum has suggested businesses implement some of the following policies:

Accept and support fair competition and a level playing field

Honour diversity and strive for continuous improvements in working conditions and employee well-being.

Integrate respect for human rights into the entire supply chain

Again, while these aren’t entirely bad endeavors, they are not capitalist in nature. The market – and those of us who participate in it – is supposed to decide which businesses succeed or fail. Because of the market, competition isn’t supposed to be fair. The only way to guarantee that it is, is to regulate and manage it. Where then, does capitalism end and communism begin?

It doesn’t seem to be a coincidence that while the World Economic Forum was positioning itself to solve the problems globalism had created, companies began instituting the very policies it was recommending. Rather than focusing on profit, today’s businesses promote diversity, equity, and inclusion while keeping score to measure their corporate responsibility and track their environmental footprint. These entities are no longer purely free enterprises, they are conduits for policy prescriptions coming from Davos.

The World Economic Forum isn’t just a venue for economic and social collaboration. It’s the governing body of a new, socially-managed economic system that relies not on the state and its citizens to manage the affairs of business but the expertise of hand-selected technocrats. Rather than individual citizens governing themselves, the elites of Davos are doing it for them.

The implications of this extend far beyond putting pronouns in your office email or buying credits to offset your carbon footprint. This represents an ideological shift away from liberal values of individual freedom, personal responsibility, and self-determination and a move towards a global, collective form of government. It’s the subversion of free market capitalism to a supranational state that is accountable to no one.

And because a global government cannot rely on traditional measures of implementation – specifically the threat of violence – the World Economic Forum has to rely on the threat of economic coercion instead. This new system is not enforced by the technocrats who created it, it’s socially enforced by the individuals participating in it.

It’s not an accident that domestic politics has become so vitriolic. It may very well be part of the design of the new stakeholder-centered economic order that’s beginning to emerge.

Final takeaway.

On paper, the World Economic Forum is just another international organization looking out for the well-being of the Earth’s inhabitants. In practice, however, the organization appears to be leading the world down a path toward global totalitarian rule.

The 20th century culminated in the competition between two rival economic systems: capitalism and communism. But those economic systems were contained. It was a competition of economic systems within and between two states – the United States and the Soviet Union – not the repudiation of the Westphalian system itself.

The turn of the 21st century changed that. When the Bretton Woods system failed, it was replaced by a managed economic system involving coordination between central banks. This created an opportunity for organizations like the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and World Economic Forum to play a larger role in the economic affairs of individual states than they previously had.

The policies created by these organizations were instituted to benefit the global good rather than the individual states and their citizens that they supposedly represented. The problem is there’s no definition of what “good” entails. It’s up to the interpretation of technocrats to decide what is good and what isn’t. In doing so, political norms and cultural values of individual states have become subordinated to the collective norms and values of global institutions.

As I noted above, Klaus Schwab’s view of the world – and his understanding of capitalism – was shaped by his upbringing in Germany. While the United States is considered an ally to most European countries, America is fundamentally not European. Our values – to include the role of private enterprise within the economy – are not aligned with the values of Europeans. Even though many Americans would agree that social well-being of all members of society is important, how that happens is the responsibility of each individual person – not the state.

Stakeholder capitalism isn’t just a redefinition of capitalism or a change to the economic order. It’s a challenge to the very essence of America itself.

Capitalism is more than an economic system. It’s also a political system. Free enterprise in America exists because our laws protect private property, the right to defend yourself, and the freedom to speak whatever is on your mind. When stakeholders’ rights supplant individual liberty, the entire entire experiment that is America comes to an end – not just capitalism.

I think this is why so many people are opposed to DEI initiatives and ESG scores. These are tangible manifestations that policies generated in Davos are becoming the policies of practice in the American homeland.

While the name ‘stakeholder capitalism’ is itself benign, the implementation of collective policies at the corporate level represents a move toward global governance that is inherently totalitarian in nature. Under totalitarian regimes, the individual is replaced by that of the state, or in this case, an international organization. You as a person ceases to exist in order for the will of the people to manifest.

This is happening. Many individuals in the United States are no longer voting, much less participating in the economy, based on their individual preferences or values. They are following an ideology that is based on collective identities and imagined communities rather than personal choice.

While the idea of a globalist conspiracy may seem irrational, the evidence of its implementation in the world around us is abundantly clear. The question we have to ask ourselves now is where with this lead. If left unchecked, individuals will be erased in an effort to promote the “greater good.” But who exactly decides what the “greater good” is and how will they enforce it?

If an economy is to be managed, someone will have to decide what that economy looks like. In Stalin’s Soviet Union, Stalin decided what was good for the people. And what he decided was good led to death and destruction for millions of people. Will Klaus Schwab and his coterie of experts at the World Economic Forum decide what is good for the rest of us?

While it’s too soon to say whether or not Trump’s America First initiative will work, the existence of such policies in the first place is something that’s worth contemplating deeper. The decision to implement tariffs and chart a new economic course didn’t come out of nowhere. More than a decade of deindustrialization and destruction of America’s economic base had something to do with it.

The pushback coming from Washington suggests this is a legitimate threat. The question now is are enough individual Americans willing to confront stakeholder capitalism before it is too late?

Independent analysis provides new perspectives on how important issues in our world today will shape the world of tomorrow.

Subscribe to Tomorrow Today to get new articles sent straight to your inbox.

Great job Amanda - This topic has been on my radar for a long while.

As a CEO with a long corporate career, and someone that works in the economic development field today, I have a comprehensive view of this thing we call capitalism and have understood what has been broken and why the WEF is yet another destructive movement by elites to gain more control of the power and money flow.

I have filtered the problem down to a couple of simple to understand flaws in how we administer capitalism today. Tariffs repair those flaws.

The first is that no definition of capitalism ever considered that jobs would become a global commodity. The idea was that some countries have materials and products that other countries do not, and some are better (read, not just "cheaper") at producing certain products. And for that we need global trade. But the concept behind democratic capitalism, it is an economic engine connected to the primary social system... this invisible hand... is that domestic labor would share in the returns of domestic capital investments. Capital moves and everyone benefit. Except when the big corporations export their production to other countries with cheap labor... then domestic capital investment does NOT benefit domestic labor. And thus the entire system malfunctions.

The other point is that capitalism requires constant healthy competition within markets. For the invisible hand of creative destruction and innovation, there needs to be the constant stress of competition. When four massive companies that are controlled by four massive Wall Street companies own more than 50% of the market share, we no longer have competition enough to support this creative destruction and innovation stress that moves the invisible hand.

There are other approaches the US government could take to fix these problems, but tariffs are the most effective, the quickest and the most just given that 170 other countries tariff US goods. They tariff US goods not because ours are cheaper, although some are, but because the US tends to produce goods of a higher quality... or at least it used to.

The latter.