The Government Seized Your Grandparents’ Gold — Could It Seize This Next?

Have you ever wondered why it’s so difficult to build wealth in America?

The short answer: wealthy people aren’t profitable.

Banks don’t like them because they qualify for low-interest rates. The government doesn’t like them because they don’t generate much taxable income. And everyday citizens don’t like them because they seem to be hoarding all the wealth.

Whether it’s the design of the financial system or pressure from your own neighbors, wealth is intentionally difficult to build. That’s why so few people have been successful in building it.

But the reason it’s so hard isn’t because you’re an undisciplined saver. It’s literally because the powers that be are seizing assets — or at the very least, access to assets — from you.

Think about it: banks siphon your cash flow preventing you from investing it. And the government will downright seize your assets if it doesn’t want you to have them.

Without assets, you can’t build wealth. It’s that simple.

This essay is a comparative analysis of how the government has historically stripped its citizens of wealth-building assets. It will first look at how an executive order issued in the 1930s made the ownership of gold illegal. It will then compare that to recent regulations in crypto.

It will argue that governments can and will seize assets when deemed necessary. In the interim, it makes it difficult for ordinary citizens to acquire assets and thus build wealth in the process. This is important to keep in mind with regard to new wealth-building opportunities emerging out of the digital economy.

In 1933, the U.S. government made the ownership of gold illegal.

During the height of the Great Depression, President Franklin Roosevelt issued an executive order calling on citizens to surrender their gold to the U.S. government. The edict was intended to limit the hoarding of gold. In practice, it made the ownership of gold illegal.

Gold has been the primary form of money throughout human history. In fact, U.S. currency was backed by gold until 1971 when President Richard Nixon took the United States off the gold standard.

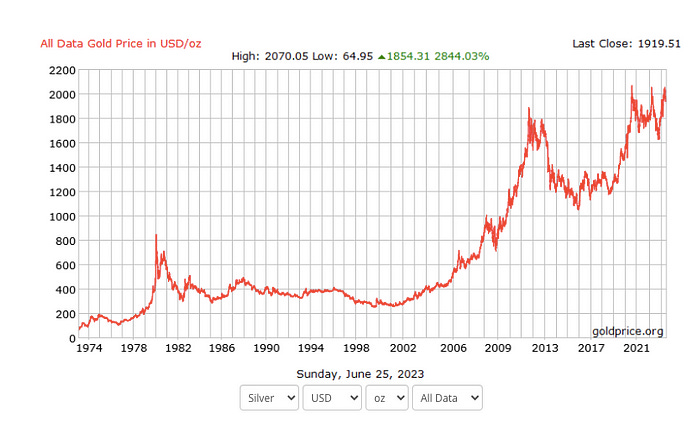

Executive Order 6102 required U.S. citizens to exchange the gold they owned for a price of $20.67 per troy ounce. Today that same ounce of gold is worth $2,000.

Gold isn’t just a form of money. It’s also an asset that holds value. In the last 50 years, gold has not returned to the price the U.S. government originally paid for it back in 1933. It’s exponentially increased in value. Anyone who handed their gold over to the U.S. government back then also forfeited the opportunity to benefit from the appreciation of gold prices in the years that followed.

The government didn’t seize its citizens’ gold without reason. It needed the capital to get the country out of the Great Depression.

Executive Order 6102 was signed into law on April 5, 1933. The initial piece of legislation that kicked off the First New Deal had been signed into law a month earlier. As gold started flowing into government coffers, public assistance programs like the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and the Public Works Administration were being stood up.

You probably learned about these programs in your high school American history class. You were taught that the New Deal helped America emerge from the Great Depression.

What you weren’t taught was how the New Deal was funded. After all, America was almost four years into an economic depression and three into a major ecological catastrophe. If income tax revenue was flowing into the Treasury at this time, it couldn’t have been much.

By seizing gold and making the ownership of it illegal the government redirected capital to itself and prevented its citizens from building wealth. That gold wasn’t just used to fund public welfare programs, it created new jobs. From those jobs, the government could rely on a new source of revenue — income taxes.

In 2023, the U.S. government is making it difficult to own digital assets.

History seems to be repeating itself. Just as a banking crisis spawned the Great Depression of the 1930s, a banking crisis led to a global recession in the aughts of the new millennium.

In 2008 an unknown individual using the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto released a white paper outlining a peer-to-peer financial system that could operate without the use of banks. This appears to have been released in response to the 2008 Financial Crisis. A year later the first cryptocurrency — Bitcoin — began circulating around the internet.

The U.S. government currently holds 1% of the circulating supply of Bitcoin. This makes it a whale or one of the largest holders of Bitcoin. What’s interesting about its whale status is that all of the government’s Bitcoin was acquired through seizures.

These seizures were the result of law enforcement activities. A significant amount of Bitcoin came from Silk Road, while other wallets were used for money laundering activities.

What is curious about these seizures is the timing. In 2019, the IRS seized approximately $700,000 worth of crypto. Today the U.S. government holds $6 billion worth of Bitcoin, the bulk of which was acquired beginning in 2020.

This, of course, comes on the heels of COVID-19, which prompted one of the largest transformations of the modern welfare state. While correlation is not indicative of causation, the buttressing of government coffers with the digital equivalent of gold during a major economic crisis is certainly intriguing, to say the least.

Regulation with regard to crypto seems to suggest the government is intentionally making it difficult for individual citizens to buy and hold digital assets like Bitcoin. Back in April, SEC Chairman Gary Gensler testified before Congress, reaffirming his belief that most cryptocurrencies are securities. In early June, the SEC announced it was suing Binance and Coinbase — two of the largest cryptocurrency exchanges — for violating securities laws.

If this trend continues, it could make it nearly impossible for crypto exchanges and decentralized financial firms to operate within the United States. The logical question that follows is: would owning crypto become illegal? If so, could that then open the door for the federal government to begin seizing digital assets from its citizens, just as it did with gold in 1933?

Final takeaway.

Asset forfeiture isn’t a new or novel idea. The government has done it before and there is no reason to believe it wouldn’t do it again.

As always, the context for doing so matters.

In the 1930s, the U.S. government was trying to get out from under the weight of the largest economic collapse in American history. For better or for worse, President Roosevelt did what he thought needed to be done to make that happen.

The present economic situation suggests we could be headed down a similar path. 80% of all U.S. dollars in circulation today were printed from January 2020 through October 2021.

This has led to widespread inflation and the devaluation of the dollar. Since 1913, the U.S. dollar has lost 97% of its value. At that rate, a U.S. dollar literally isn’t worth the paper it’s printed on.

This is happening at a time when a fundamental economic transformation is underway. Thanks to new general-purpose technologies much of the U.S. workforce will be unemployable in the years to come.

An alternative to income will have to be created. Under present conditions, it’s uncertain whether or not the government will be able to finance such an alternative as it did during the New Deal era.

Digital asset forfeiture could be required to finance government-sponsored welfare programs in the imminent future.

This raises significant questions about what property ownership looks like in a digital world. Could the government compel tech companies like Microsoft or Google — the entry points to a number of DeFi platforms — to relinquish data about their customers? Could that data then be used to seize digital assets?

Could ownership of digital assets become illegal altogether?

History tells us it’s possible. The question is will it?