Who Should Pay for Fat People?

Obesity is on the rise but so is a push to accept healthiness at any size. The costs of managing obesity are becoming unsustainable. So who should pay for it?

Fat acceptance has become the latest cause du jour.

In a recent interview on The Joe Rogan Experience, long-time fitness advocate Jillian Michaels argued fat acceptance is nothing more than a psyop to convince society that anyone can be healthy at any size:

But if you believe in the veracity of science, you know that obesity is highly correlated with a number of chronic diseases. It’s the leading risk factor for type-2 diabetes and is a major factor for heart disease, the leading cause of death in the United States.

Simply put it’s biologically impossible to be both fat and healthy.

Obesity is a death sentence. After years of abuse, your body reaches a point where it can no longer support itself. Eventually it kills you. That’s why millions of people die from it every year.

Yet that isn’t stopping the trend to normalize it in culture. The word “obesity” is now considered a slur, deserving of the same outrage as uttering the N-word. And city governments are paying top dollar to hire “body positivity” advocates to “destigmatize” obesity.

Obesity isn’t something to accept. It’s an epidemic that has severe long term consequences if it’s left unaddressed.

Consider this: in 1990, only 12% of Americans were considered obese. By 2005, that number doubled to 23%. Today 74% of adults are considered overweight while 43% are obese.

I was born in 1991. That means in my lifetime the rate of obesity has more than tripled. Being healthy is now exceptional.

Food is largely to blame. The typical American consumes around 3,600 calories per day. Most of that comes from ultra-processed foods that are laden with sugar and engineered to be as addictive as possible.

Policymakers know this. That’s why there’s been attempts to curb obesity by punishing food manufacturers and distributors. In 2012, former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg instituted a 16-cent tax on soda. A few years later, Philadelphia implemented its own beverage tax of 1.5 cents per ounce on sweetened caloric and non-caloric beverages.

Those efforts haven’t worked. 60% of adults in New York City are overweight or obese while 67% of adults in Philadelphia fall into the same category.

But obesity isn’t just a public health crisis. It’s an unacknowledged economic crisis too. Obesity lowers productivity and puts a tax on public welfare. 23% of SNAP dollars go towards sugary drinks and desserts while 80% of SNAP beneficiaries qualify for public-funded health coverage including Medicaid and CHIP.

To put it bluntly: you’re paying for people to drink soda and then you’re paying for the health complications that come as a result of it.

Obesity is a byproduct of lifestyle. Those who develop obesity largely do so by choice. While genetics may play a role in one’s disposition to becoming overweight, at the end of the day no one is holding a gun to your head forcing you to consume 3,600 calories per day. That’s a choice.

Obese patients cost more when they go to the hospital, they take more medications, and they consume more food. There’s an unspoken cost to being obese which raises an important question. If obesity is the byproduct of lifestyle and individual choice, who should ultimately pay for it? The taxpayer or the people engaged in gluttony?

That’s what this essay will dive into. Obesity comes with added costs that put pressure on the health care system. Because the healthcare system is both directly and indirectly subsidized by taxpayers, one way or another, we’re all paying for obesity.

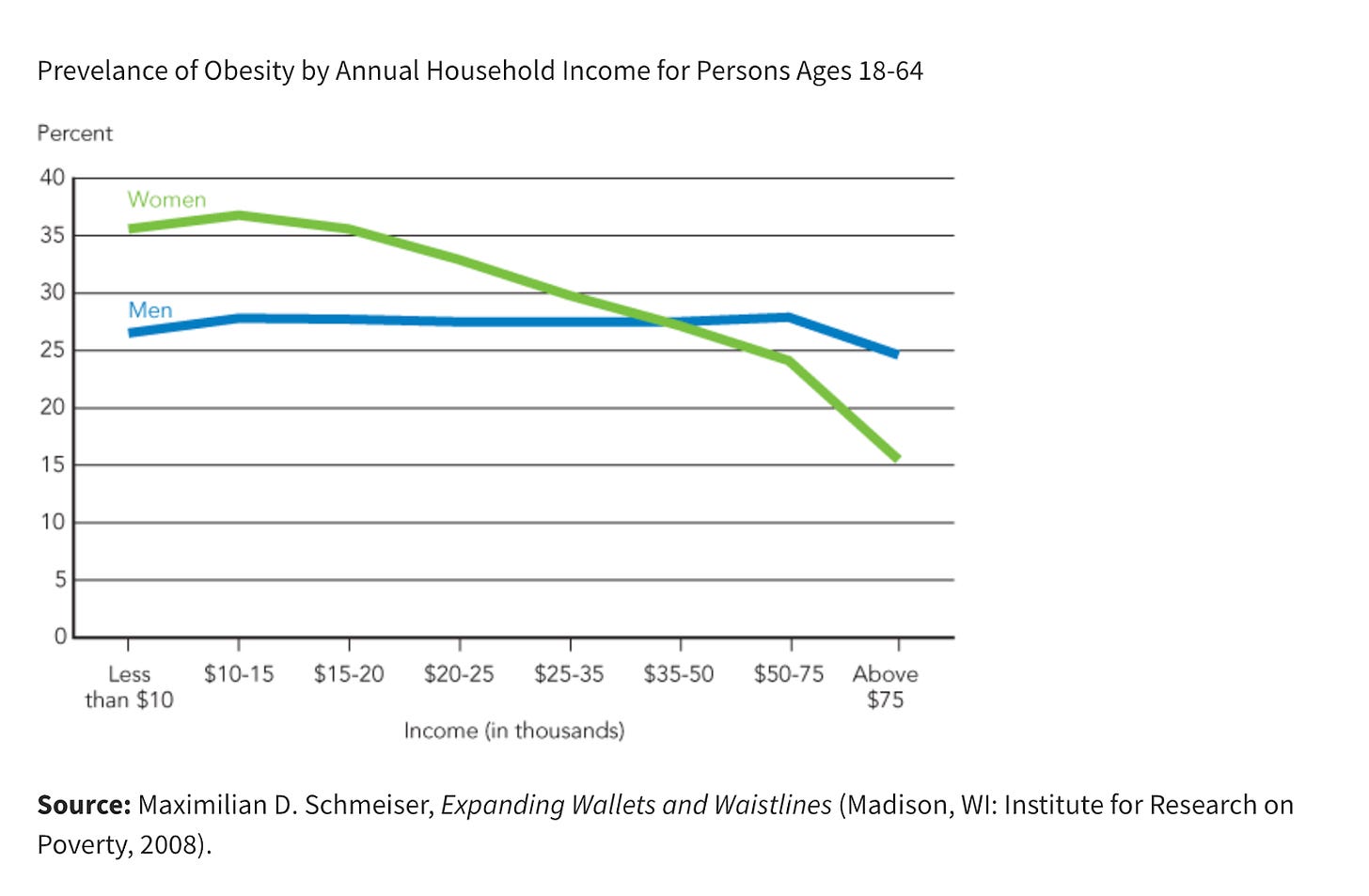

As the rate of obesity increases, so will the costs associated with it. Half the population is projected to be obese by 2030 with low-income households experiencing higher levels of severe obesity. The vast majority of these people will be recipients of taxpayer-funded benefits.

Obesity isn’t sustainable and normalizing it isn’t a solution. Within the next decade there will be far too many obese people relying on a system that can no longer support them. What will we do then?

The United States spends more on healthcare and has a higher rate of obesity than other developed countries. This suggests obesity – and the chronic illnesses that stem from it – are a key driver for rising healthcare costs.

There’s no doubt that the American healthcare system is broken. The average cost of a health insurance premium for a family is $25,572. Without insurance, a trip to the ER will run you $2,715. It’s no wonder that 58% of all consumer debt in the United States is medical debt.

These costs stem from unhealthy individuals relying on a corrupt healthcare system to treat chronic conditions. In her book Good Energy, Dr. Casey Means argues that 93.2% of adults suffer from metabolic disruption which leads to chronic issues like diabetes and heart disease. Because there’s no profit to be made from healthy people, there’s a perverse incentive to keep everyone as sick as possible.

The root drivers of obesity – poor diet and nonexistent exercise – have largely gone unaddressed as a result. This affects everyone who participates in the healthcare system.

According to the CDC, obesity costs the American healthcare system $173 billion per year. That means per year, Americans are paying a de facto $1,018 tax to manage obesity. This is on top of whatever you pay out-of-pocket to cover your own medical needs.1

The United States currently spends 17.6% of its GDP on healthcare, more than any other developed country. This spending is correlated with a high rate of obesity, suggesting that obesity is the primary driver in healthcare spending.

Obese people take a toll on the healthcare system because they’re more expensive to treat. According to an NIH study:

The annual medical care expenditures of adults with obesity ($5,010) were double that of people with normal weight ($2,504). The effect of excess weight on annual medical care costs at the individual level increased significantly with class of obesity; relative to those with normal weight, the additional expenditures due to obesity rose from $1,713 (a 68.4% increase) for class 1 obesity to $3,005 for class 2 obesity, (a 120.0% increase) to $5,850 (a 233.6% increase) for class 3 obesity.2

Being overweight increases the likelihood of developing a chronic disease like diabetes and heart disease. Those diseases result in a higher number of trips to the doctor’s office and more medications to manage symptoms.

Obesity amplifies the costs of providing medical care. The heavier you are, the harder it is to physically move you and treat you. Ambulances and hospitals alike need specialized equipment and often require more personnel to move large people. This makes an ambulance ride 2.5X more expensive for obese people than the average person.

Once in the hospital, an obese patient will need more of almost everything to treat whatever they're dealing with: more medication, more anesthesia, more hands-on assistance, and more time to recover.

The costs and the risks of treating obese patients drives everything else up. All of this is compounded by socioeconomics. The poorer you are, the more likely you are to also be obese. That means the more obese you are, the more likely you’re going to rely on publicly-funded healthcare like Medicaid to cover routine medical care as well as trips to the hospital for sudden complications like a heart attack.

This doesn’t just put pressure on the healthcare system, it puts pressure on taxpayers to continue funding rising costs within the system. That same NIH study referenced above shows that obese patients on public health insurance plans like Medicaid cost more to cover:

The increase in medical expenditures of adults with obesity compared with those with normal weight covered by public health insurance payments ($2,877) was greater than for those having private health insurance ($2,058).

Obesity is a chronic condition which means it’s sustained over a long period of time. While treating obesity puts direct pressure on the healthcare system and the taxpayers who fund it, it also puts downward pressure on the economy.

Obese workers who have chronic medical conditions are a liability to their employers. It costs more to insure them and because obese workers are more likely to take time off work to tend to medical issues, they’re less productive. A study looking at productivity found that:

Compared with employees with normal weight, individuals with obesity missed more time from work and worked less productively, resulting in higher indirect costs.

This is why fat acceptance, particularly in places of employment, is a problem. Healthcare is a huge cost for employers. Back in October, The Wall Street Journal reported just how expensive healthcare has become:

The cost of employer health insurance rose 7% for a second straight year, maintaining a growth rate not seen in more than a decade, according to an annual survey by the healthcare nonprofit KFF. The back-to-back years of rapid increases have added more than $3,000 to the average family premium, which reached roughly $25,500 this year.

Obese people have chronic health issues that cost more to treat. And if their obesity prevents them from performing at a high level, the direct costs of lost productivity and higher premiums are passed onto other workers.

Large employers can raise premiums for everyone to absorb the costs. But small- and medium-sized businesses can’t continue paying higher rates. This is one reason why AI adoption is accelerating. AI isn’t just more productive, when it comes to healthcare, there’s a real cost savings that employers are eager to benefit from.

I hope by this point you can see the logic of where this is going. Eventually employers will stop providing health insurance coverage altogether. The burden then will be placed on the public healthcare system. But because the costs and prevalence of obesity are concentrated in a demographic that isn’t contributing to the economy – or at least, contributing as much as they could – it’s going to require healthy people to foot more of the bill. If trends continue, within the next decade, there will be fewer healthy people supporting a growing number of obese people.

There’s no question that the healthcare system is broken. But the obesity epidemic is making it unsustainable. At some point in the near future, the system as it’s currently set up will be insufficient to manage the costs. Who then is supposed to pay for obesity?

Final takeaway.

This isn’t a question about accepting fat people or allowing them to be their “authentic” selves. It’s about acknowledging there is a real crisis in the United States when it comes to obesity.

Obesity is fiscally unsustainable. The path we’re on leads to higher costs and less coverage for everyone. Under the current system, the people who will be expected to shoulder these costs are the ones who are economically more productive and generally don’t have the same chronic conditions that obese people do.

Like other social issues, this isn’t politically palatable. Rather than bringing people together, it will add another point of division within society.

Asking someone who goes to the gym regularly and eats their fruits and vegetables to subsidize the medical costs of someone who’s morbidly obese is a tough sell. Especially when you acknowledge that many obese people are victims of choice rather than genetics.

The system is already buckling. Within the next decade, it will reach a point of instability. Two outcomes could emerge as a result.

First, obese people may be taxed for being fat. It’s clear taxing the foods obese people eat hasn’t worked. Instead of taxing the food, the government could implement a fat tax against individuals who are obese.

In the same way Americans self-report income to file their taxes, a fat tax would require citizens to self-report their weight. Using BMI, assessors at the IRS could levy a tax or BMI could be a condition to qualify for programs like Medicaid and food stamps.

Back in 2007, an Australian economist evaluated this idea for the American Enterprise Institute. In an op-ed he wrote:

This system would operate smoothly through the IRS, as everyone would submit an official Body Mass Index (BMI) report with their annual tax return. The IRS would make the fat tax calculation for you.

It would be a progressive tax: the fatter the taxpayer, the higher the tax. The top of the “normal” range for BMI is 24. A BMI above 25 would pay a small surtax, say 5 percent, BMI 30s would pay 10 percent, etc.

While a fat tax may seem harsh, it might be necessary. Obesity is a product of lifestyle. According to one study, financial incentives do impact weight loss. If there’s a financial cost to being fat, it could make being fat undesirable.

Under the current social climate where fatness is expected to be accepted, implementing a fat tax is unlikely. Instead, we might see the creation of a two-tier health system, something that has already started to emerge.

Thanks to a combination of wearables, health data, and AI, it’s becoming easier for individuals to manage their own health. Companies like Function Health will give you access to your metabolic data for a relatively low fee. With that information, individuals can develop plans to manage their health on their own.

This could lead to the rise of sovereign patients. Rather than relying on a broken medical system, individuals will opt out of it altogether. They’ll piece together a bespoke healthcare plan that meets their needs, rather than the needs of an unhealthy population.

Sovereign patients would manage lifestyle-related chronic illnesses on their own but would still rely on the medical system for some routine appointments and emergencies. But instead of using health insurance, sovereign patients would pay for the costs out of pocket.

There are several ways to do this. Transparent pricing is making it easier for patients to shop for treatment on their own. Amazon One Medical offers virtual visits for a fraction of the cost of taking a trip to your local urgent care. At $49, you can request a telehealth appointment to get treated for strep throat. If the doctor prescribes penicillin, it’ll cost you anywhere from $11 to $35, depending on the dose.

Acute emergencies would still pose a high financial risk for sovereign patients but that could be mitigated with a healthshare. Healthshares are alternatives to health insurance where members pool resources and distribute costs based on need. I myself am currently enrolled in a healthshare. I pay $194 a month and if I needed to take a trip to the ER, I wouldn’t pay more than $1,000 out of pocket.

Religious communities are known for this option. The Amish, for example, are uninsured. When someone needs a surgery or has to undergo treatment for cancer, the community pools its resources together to cover the cost.

I think this model will become more mainstream and will inevitably create a two-tier health system. Those who can afford to opt out will, while those who rely on the existing system will increasingly find themselves burdened by the costs of treating a sick population.

The healthcare system as it is isn’t sustainable. Because health insurance is tied to employment, AI adoption will have an incredibly destabilizing effect. Fewer people will qualify for employer coverage, transferring the costs to the public healthcare system. Obesity is projected to continue rising as people lose jobs and become more dependent on the government’s safety net.

Something has to change. No one wants to have this conversation but in light of the push for greater fat acceptance maybe it’s time we start talking about the obvious elephant in the room.

Someone has to pay for fat people. The question is who should be responsible for it?

☕ Thank you Tomorrow Today subscribers.

Your support makes it possible to share thoughtful commentary like this about how the world is rapidly changing and the things you can do to prepare for all the changes that lie ahead. Become a subscriber to show your support.

I should note this isn’t a direct tax. You’re not literally paying $1,018 out of pocket. Instead, this comes out of your annual tax bill. When Congress raises your taxes or takes on debt to fund healthcare programs, you’re indirectly paying for it.

According to the study, obesity is divided into three categories: BMI was calculated using self-reported or proxy-reported (for another household member) height and weight. Obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 and divided into classes for adults: class 1 (BMI 30 - < 35 kg/m2), class 2 (BMI 35 - < 40 kg/m2), and class 3 (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2).

📩 Become a Tomorrow Today Subscriber

Stay informed with independent analysis on major shifts shaping our future. As a subscriber, you'll get exclusive weekly insights you won’t find anywhere else. Subscribe today to read all of the essays in the Tomorrow Today library.

This seems like a simple question, but I think the subject is more complex. But as a first attempt, let's focus just on the healthcare aspect, e.g. who should pay for healthcare for people who are overweight. In the US, healthcare is a shared cost, generally, with people paying some amount personally (via cash, copays, insurance premiums etc), with some amounts being paid by employers and some by government at various levels. The specifics vary a lot, with the poorest paying the least share out of pocket, and the richest paying the most. I think your argument is generally that "fat" people are more expensive than lower weight people for the government portion of healthcare expenditures, and that it is that portion of their cost you care about (the public burden portion). And your base argument is that their condition is a choice, and because it's a choice it shouldn't be a public burden.

That same "your choice" argument could be used for drug overdoses, motorcycle or scooter accidents with head injuries, auto accidents by speeders, smoking related lung cancer, heart attacks due to lack of cardio exercise by thin people, people who jay walk and get hit by a bus, run of the mill measles by people who chose to forgo vaccination, etc. As a society we'd have lower shared burden medical costs, and a lot more people dying on the streets and sidewalks. So, if you can put a label on it, and say "it was their choice" and deny care, then only people of financial means will have care, because everyone who suffered a health event due to a "choice" would be denied the public cost sharing portion. I'm not sure that's actually what people want, but perhaps it is. Hard to think of something that can't be labeled a "choice" at some level.

You could also look at "fat" as a spectrum. If your BMI is 25.1. should you pay a little more than a 'non overweight' person. If your BMI is 26? When it's 30 and classified as obese should you be charged a higher fee at the doctors office, or higher insurance. Or at BMI of 35? And what about the anorexic patient or the cancer patients wasting away. Should they get rebates because they are thin?

Or we could look at the public policy aspect. Since approximately 74% to 76% of adults in the United States aged 25 and older have a BMI over 25, meaning they are classified as either overweight or obese, this is a huge voter block. Do you think it's likely that 3/4s of the US voters would vote to penalize themselves by decreasing the public share of their health care costs? Particularly when it is the "catastrophic insurance" coverage portion that can keep them out of bankruptcy or death?

Another way to look at Approximately 74% to 76% of adults in the United States aged 25 and older have a BMI over 25, meaning they are classified as either overweight or obese, is to say that 3/4s of US adults are already paying their "fair" share, and 25% are paying more, or overpaying. Kind of like men paying for pregnancy, or women paying for prostate cancer care. In the public portion you pay a share for things that personally you may not suffer. That's just the yin/yang of public services.

On recent flight from DC to Sacramento it was shocked at the number of XXL and XXXL passengers. Thankfully my 115 lb wife did not take up much room in the center seat, because the kid next to her was 300 lbs with much of it spilling out into her seat space. The guy in front of me was so big that he about knocked my laptop off my tray table every time he leaned back… and I was in extra legroom class seats.

My problem is that we have friends who are fat. I have brothers that are overweight. I have cousins, nieces and nephews that tip the scales. My new daughter in law and my other son’s live in girlfriend are big. I have to keep myself from any judgement. My wife and I, and our two sons, have always stayed fit and healthy body weight. It bothers me because it is a sign of weakness… lack of self control. The people at the airport standing in line for pizza and Chick Fil-A far exceeded the lines where fresh salads could be purchased. The portions people eat are huge. The only fast food I get is and In-and-Out protein style burger, or Subway turkey and avocado on flatbread or a wrap… with lots of veggies and mustard only. I don’t eat a lot of carbs… except some rice. I am a home chef, so we eat well. Made chicken piccata tonight, with roasted summer squash from the garden. Smaller portions. Apples, oranges, grapes, celery and carrots for a snack. Maybe some humus dip. I walk. It isn’t that difficult. I do love cheese, but again, smaller portions.