The Economy is Adding New Jobs — But Not Where You’re Looking

Tech, finance, and media were the top industries to shed jobs in 2023. But those industries aren't creating new jobs. Here's where the vast majority of new jobs are actually being added.

There are two economic indicators that financial analysts, policymakers, and C Suite executives all look at to gauge the state of the economy: interest rates and the monthly jobs report.

On the first Friday of every month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics issues a jobs report. The report highlights month-to-month changes in job growth, wages, and unemployment. It also provides a snapshot of the state of the economy from the perspective of labor and human capital.

The data points in the report can be some of the first indicators pointing to a recession. If this information isn’t managed well, it can get out of control, stalling the economy.

A decrease in jobs results in decreased earned wages and increased demand for unemployment benefits and other social services. Smaller paychecks mean less discretionary income for workers to spend on goods and services, creating a dangerous spiral that can lead to even more layoffs.

This is why a lot of people pay attention to the jobs report. It’s usually a better indicator of how things are going on Main Street. But it isn’t perfect.

The jobs report simply counts the number of new jobs being created. It tells you where these jobs are being added but not the types of jobs being created. The quality of those new jobs matters more than the number itself.

Job growth may be happening, but it’s not necessarily happening for everyone. This essay is going to look at where job growth is actually taking place in the economy. It will reveal that there is a misalignment between the demand for workers and the supply of labor available to meet demand.

If you’ve been out of work for a while and are frustrated by your job search, that’s because you’re looking for a job in an industry that is no longer creating new jobs. Paying attention to the jobs report will reveal job creation is highly concentrated and isn’t being equitably distributed across the economy.

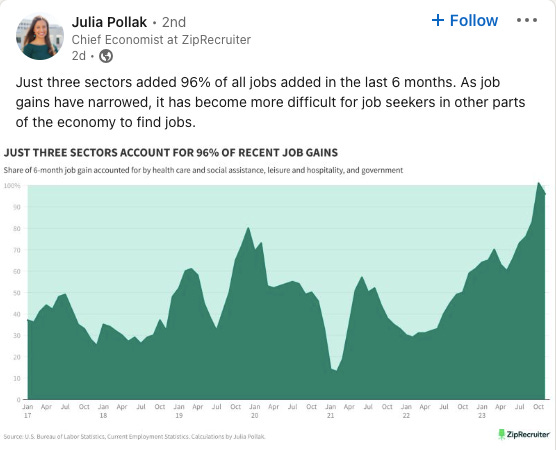

96% of all jobs created in the last six months were added in just three sectors of the economy. Those sectors aren’t necessarily creating high-paying jobs.

ZipRecruiter’s Chief Economist recently dropped the following statistic on LinkedIn:

While the headlines have been filled with news of layoffs in tech, the vast majority of jobs in the last six months have been created in health care and social assistance, the government, and leisure and hospitality.

Zooming out to look at the rest of 2023, 81% of all jobs created went to those same three sectors, as well as private education.

That means only four industries are providing any form of job growth in the economy.

That’s a stunning figure to pay attention to. While jobs are, in fact, being created, the qualitative data suggests job creation isn’t being equally distributed throughout the economy. Instead, it’s being highly concentrated in sectors where jobs are certainly available but likely not desired.

Take health care and social assistance as an example. While you might assume job growth applies to highly-skilled jobs like surgeons and anesthesiologists, those only consist of a small fraction of the broader healthcare sector. There’s a greater abundance of jobs for low-paid work like home health aides, nurses, and administrative assistants.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the demand for home health aides is growing “much faster than expected.” With a projected growth of 22% over the next decade, there’s going to be greater demand for low-paying jobs like home health aides compared to higher-paying jobs, like surgeons and physicians, which is only projected to grow by 3%.

This makes sense, of course. Baby Boomers are aging, while robots and automation are changing the demand for specialized surgical skills. The demand for low-paid work in healthcare is going to rise over the next decade because there are demographic and technological catalysts reshaping the nature of work in healthcare.

This is true in all industries, not just healthcare. The problem is that the new jobs being created aren’t necessarily valuable jobs. The pool of available talent looking for work isn’t going to be inclined to take the jobs that are in demand.

The median wage for a home health aide, for example, is only $14.51. That is less than what someone could expect to make working the burrito line at Chipotle, babysitting on the weekends, or becoming a dog walker. If a worker has a choice between making burritos or changing dirty adult diapers, they’re going to choose burritos.

This might be just one specific example, but it reveals that not all jobs being created are good jobs. They might be needed — and they might be necessary — but they aren’t in alignment with the demand for work coming from the labor market itself. Just because you create these new jobs doesn’t mean the workers will come.

Workers need to start paying attention to where the jobs are actually being created — not where they want them to be.

The presence — or absence — of job growth is a far better indicator of how things are going in the economy than just the volume of jobs being added each month.

According to an interview in Axios, Ms. Pollack argues:

“Job growth has pretty much ground to a halt in most of the rest of the economy, and that is mostly by design,” said Julia Pollak, chief economist at ZipRecruiter, referring to the way the Fed’s rate hiking campaign has cooled things off.

When this happens, it can stall the rest of the economy. Fear and decreased revenues can spark even more layoffs in anticipation of an inevitable economic downturn.

Over the last year, tech led the way in layoffs by shedding some 163,000 jobs. Media, retail, and finance are other notable industries that experienced sizable layoffs. Looking ahead to 2024, many industries are now holding steady by not hiring at all.

What makes this particularly challenging is that positive job growth reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics is fundamentally misaligned with the labor market. The jobs that skilled workers need and want aren’t necessarily the jobs that are being created.

Workers like laid-off techies and newly-minted college graduates aren’t going to take jobs working as home health aides or hotel front desk clerks.

Instead, these types of workers will continue fighting for a shrinking number of jobs that are increasingly being eliminated or automated thanks to rapid advancements in artificial intelligence. It’s no surprise that job seekers feel discouraged — they’re looking for jobs that simply no longer exist.

This is why it’s important to pay attention to the nuance that’s often missing from government data. Job growth for the sake of job growth is insufficient. The quality of jobs being created is arguably more important.

The future of work is unfolding now, right before our very eyes. Job creation is just one part of the shift that’s happening. There is a misalignment between the talent that’s available and the employers looking to pay for that talent.

As a worker, it’s up to you to look for demand signals pointing to the shift in work that is available.

Final takeaway.

Learning how to read economic data is going to be a valuable skill in the digital transformation that’s underway.

It’s important to look for signals in the economy rather than just taking what you’re being told for granted. You need to be able to discern the truth from those signals and be prepared to take action on what you uncover.

Quantitatively speaking, the number of jobs available in the economy is growing. The quality of those jobs, however, is up for debate.

While tech was hot over the last decade, it is not impervious to the laws of supply and demand. New technological advancements, combined with economic policy constraints coming out of the Federal Reserve, are making high-paying jobs less lucrative for employers to offer.

While technically demanding and highly-skilled work may continue to generate large salaries, that won’t be the case for a number of jobs in the white collar economy (I’m talking to you, project managers).

Throughout history, the expectations of workers have often clashed with those of corporate shareholders and the managers tasked with maximizing profitability. This is nothing new. But it doesn’t mean it isn’t happening.

Part of adapting to the future of work means being more malleable than ever before. You have to move to where the jobs are actually at, not where you want them to be.

It’s abundantly clear that only a few sectors of the economy are generating new work. While there may be some opportunities for high-value work, especially in disruptive health tech startups or newly established biotech companies, this isn’t going to be the case for many of the jobs being created. It’s likely the supply of work reported in the monthly jobs report is for low-value employment that cannot yet be outsourced to robots or intelligent algorithms.

Workers need to be open and willing to flow in and out of different sectors of the economy as it continues to grow and evolve. The best way to do this is to start looking for signals and begin creating proof of value for yourself.

It’s up to you, the worker, to take action for yourself moving forward.